The Psychology of Sacrifice

Why Middle-Class Parents Are Buckling Under the Weight of Aspiration

When I visited India earlier this year, I didn’t expect to be thinking about school fees. But there I was - in the joyful, noisy chaos of a crammed, multigenerational home, surrounded by barefoot cousins and endless cups of chai - quietly spiralling. What struck me wasn’t poverty. It was confidence. The children I met, though they had little, carried a calm certainty that life would be better for them than it had been for their parents. That intergenerational optimism - so deeply stitched into the social fabric - caught me off guard. And, frankly, it unsettled me.

Back home in Brighton, on the school run, I found myself looking at my twin daughters in the rear-view mirror - ten years old, funny, bright, emotionally fragile in that way only preteens can be - and wondering: Do they feel that same confidence about the future? Do I?

Like many middle-class professional parents in Britain, I’m clinging with white-knuckle intensity to a version of the “good life” that places a big bet on education. My daughters attend an exceptional - and exceptionally expensive - private school. I’ve calculated (and re-calculated) the cost of getting them through to the bitter end. The number is enormous. The VAT increase this year, a thrilling development.

By day, I research investments in emerging markets; by night, I’m training to become a psychotherapist. My wife, a dental nurse, is returning to work to contribute. By most measures, we’re incredibly fortunate. But the psychological load of this carefully constructed future is heavy.

There’s a well-known idea in psychology called the sunk cost fallacy - the tendency to keep pouring resources into something simply because we’ve already invested so much. It’s why investors hold onto failing stocks. It’s why people stay in bad jobs or worse relationships.

Private education, for many of us, is exactly this kind of emotional investment. Once we commit, we structure our lives around it. We work harder, stretch ourselves thinner, and swallow mounting anxiety - all while clinging to the belief that it must be worth it. Because if it isn’t, what then?

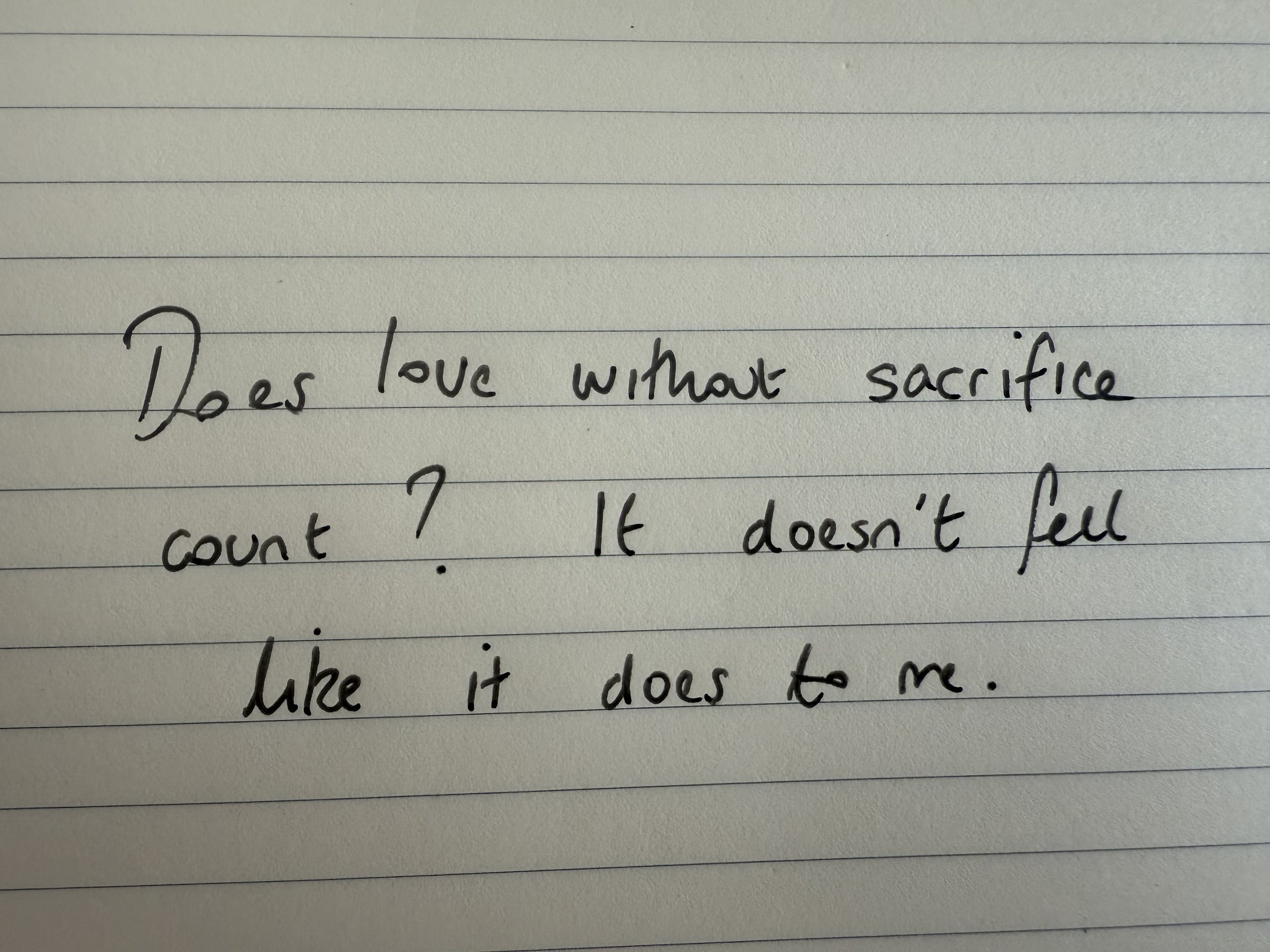

And beneath the spreadsheets, something deeper gnaws at me - a sense that I’m not just funding their education, I’m staking my identity on it. This, I’ve come to realise, is one of the great unspoken truths of Britain’s professional middle class. We are not just investing in our children’s futures - we’re investing in our own narratives. That we worked hard enough. That we did the best we could. But how far is too far?

Enter another psychological trap: the control fallacy - the mistaken belief that I am either entirely responsible for everything that happens, or utterly powerless. Climate instability, AI disruption, polarised politics - the world they’re stepping into feels more uncertain than the one I inherited. Private education isn’t then a service, it becomes a seductive illusion that enough sacrifice will protect my daughters from the chaos.

The reality is that my daughters are getting a brilliant education. My daughter recently developed a life-altering disability, forcing her to relearn how to write. The compassion has been humbling but the individual care she’s received has been extraordinary.

But this isn’t a story about the virtues of small class sizes. It’s about parents who, from the outside, appear to have it all - but are quietly unravelling under the emotional and financial cost of trying to secure their children’s place in a world that no longer feels secure.

I don’t want advice on school catchment areas, and certainly not sympathy on fees. But I do want to know if anyone else feels it too - this quiet panic under the surface that my confidence in the future is shaken.

I also want to name the contradictions we all carry: wanting to give our children every opportunity, yet resenting the performance treadmill it creates - for them, and for us. Thinking good parenting is synonymous with over-functioning, and that pulling back would be an act of selfishness. And yes, it’s about class, too. Social mobility has stalled. If we fall, will our children ever get back?

I want to believe my daughters will grow into a brighter future. And I know it won’t be defined by the school named on their UCAS form - this will likely count against them. I also know my success as a parent will depend on whether they’ve seen joy, resilience, and a sense of “enoughness” modelled at home.

But belief is one thing. Behaviour is another. And despite retraining as a psychotherapist - as part of my efforts to understand the architecture of human motivation - I’m still on the treadmill. Still calculating. Still clinging. Maybe the best thing I can do now is step off and save up for the therapy they’ll inevitably need to recover from my parenting.

Photograph from Jaipur, India February 2025