Why Schools Should Teach Jazz, Not Classical

In a world obsessed with the straight path - five-year plans, upward graphs, neat progressions — change can feel like collapse.

A career pivot? Backtracking.

A pause to care for someone? Lost momentum.

A gnawing sense that something no longer fits? Maybe you’re just being flaky.

But maybe change isn’t the disruption of life.

Maybe it is life.

The rhythms of modern adulthood - especially for women - almost demand recomposition. Parenthood, partnership, caregiving, ambition, reinvention: it’s not a clean sequence. It’s a loop. A layering. A back-and-forth that doesn’t fit neatly on a timeline or a CV. And yet, it’s real. It’s alive. And it’s often the very space where meaning grows.

The challenge isn’t the change itself. It’s learning how to stay steady while adapting - to remain in conversation with your life as it shifts. Without the thread of meaning change can feel reactive. Meaning gives coherence to what can otherwise feel random or reactive.

“We are not what we know but what we are willing to learn.” This isn’t just a quote by Mary Catherine Bateson. It’s a mindset. It’s what allows change to feel like motion, not failure. It’s what keeps you reflective rather than reactive.

This idea sits at the heart of Bateson’s 1980s book Composing a Life. She writes about five women - including herself - whose lives didn’t follow ladders, but loops. They rerouted. Rewove. Restarted. They balanced love with work, care with ambition, clarity with uncertainty. Not perfectly. But meaningfully.

The book doesn’t celebrate chaos. It honours the quiet, ongoing work of recomposition - the practice of making a life out of what’s real, not what was planned. And in doing so, Bateson offers a gentler, truer lens: that growth often looks like interruption. That feeling lost at times can sometimes mean you’re finally listening.

Therapy, Self-Awareness, and Making Sense of Change

This is the work many people come into therapy to do - not to “get back on track,” but to ask whether the old track was ever really theirs.

Meaning doesn’t require staying the course. Sometimes it requires changing it. And that takes self-awareness: to notice when an old story is no longer working, and the courage to stop performing it.

Therapy supports this kind of authorship. Not by rewriting the past, but helping people make sense of it - by finding coherence, and build something new.

Reflection isn’t indulgent. It’s a form of emotional literacy. Because unless you can name the deeper thread in your life, it’s hard to hold your nerve when the next change arrives.

I’m writing this in midlife, and so have had time for several rewrites. Chances are you’ve watched dreams shift too. You’ve made choices that no longer make sense. Or built sense around choices that were never fully yours before evolving again.

Society often treats these changes as collapses. But we don’t have to. We can treat them as second or third compositions. Not redos. Not failures. Just new movements in a longer piece.

Bateson invites us to think like jazz musicians - improvising our way through life, not because we lack structure, but because we’ve learned to stay in rhythm as the song evolves.

Mid-life is often a time to finally be able to do this. Enough life behind to gather data. Enough life ahead to make something of it. The task isn’t to panic or patch. It’s to get curious. To ask what still fits - and what’s waiting to be reimagined.

Perhaps this is why therapy can feel like such a shock? Because it’s the first place that gives you permission to improvise — and someone who helps you make sense of it, and believe in it.

Why Don’t We Teach This Earlier?

If therapy helps us recompose, why isn’t that mindset woven into our education from the start?

Why do we wait until adulthood - or burnout - to give ourselves permission to question the path we’re on?

We’ve grown up in a world that values that rewards consistency over adaptability. An education system built for those who choose a track and stick to it, and do so early. Careers advice framed as a destination, not an unfolding.

And yet the world we’re handing to young people doesn’t work like that anymore.

They’re stepping into a job market shaped by the gig economy, by automation and disruption, by roles that didn’t exist five years ago and might not exist five years from now. Their careers won’t be ladders - they’ll be patchworks. And their ability to compose, decompose, and recompose will be their greatest asset.

So why not teach improvisation? Why not teach meaning-making?

Why not normalise sabbaticals and reinventions - not just with slogans, but with frameworks?

Instead of asking a 16-year-old what job they want, we could ask: What kind of problems do you want to help solve? What kind of life do you want to build - and how will you know when it’s time to rework it?

This is the stuff of therapy, often miscast as “soft.” But it’s not soft anymore.

It’s core curriculum content. It’s survival.

Because in a world this fast, this fractured, and this fluid, the most essential skill isn’t productivity. It’s adaptability with integrity.

This is what we should be teaching: how to stay rooted in yourself - and what matters to you - while the shape of your life keeps shifting.

Embracing improvisation around this core sense of self. Because improvisation doesn’t mean you’re lost. It means you’re listening. Staying awake to what’s changing. Responding with courage.

The women in Bateson’s book didn’t follow maps. They wrote them, mid-stride. They adjusted. They risked. And they kept showing up to the next version of themselves.

Which might just be the most honest definition of growth we have.

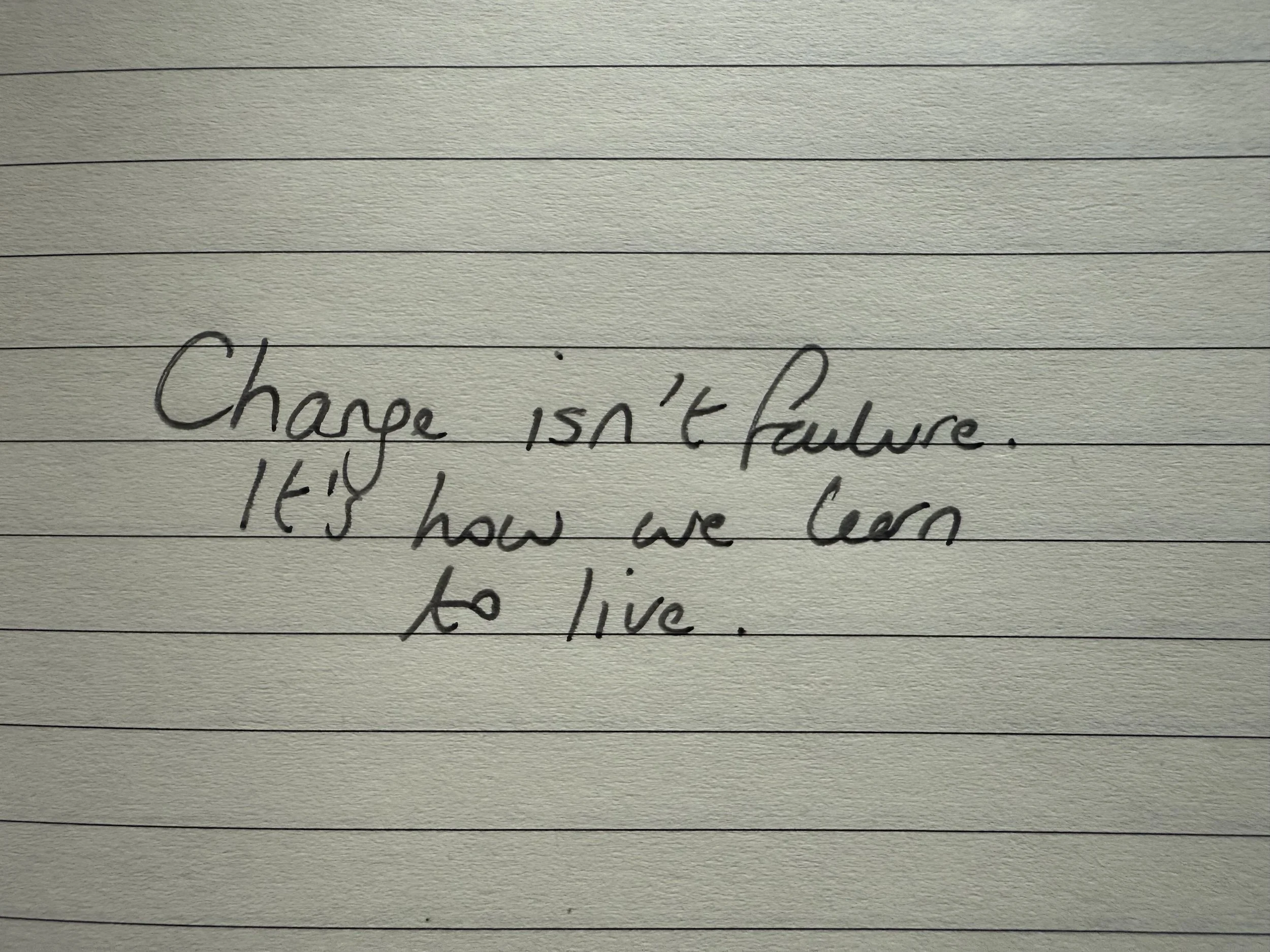

Change is not failure.

It’s feedback.

It’s movement.

It’s how we learn to live.